Participatory policymaking offers ‘disruptive’ response to climate change

/One of the newest flagship programs of People Powered is its Climate Democracy Accelerator (CDA), in which civil society organizations wanting to use participatory democracy to counter climate change are paired with expert mentors (supplemented by the Participation Playbook ), attend customized workshops and receive implementation support.

The first cohort of the CDA has “graduated,” and some members are now completing their projects. People Powered Communications Director Pam Bailey recently interviewed one of the participants: Kudzaiishe Seti, programs officer for Zimbabwe’s Green Institute. Joining him for the interview was Mateusz Wojcieszak, his mentor and board chair for Poland’s Field of Dialogue Foundation.

Why is climate change such a pressing issue for Zimbabwe?

Kudzaiishe: In 2019, when Cyclone Idai struck, people were not prepared. The devastation was massive, particularly among internally displaced people (IDPs) and refugees. In Chipinge District, where the Tongogara Refugee Camp is located, over 2,000 houses, mostly built with mud bricks, were completely or partially damaged and over 600 latrines collapsed.

We want to prevent that from happening again.

Cyclone Idai damage in Zimbabwe

Another big concern is that this district is highly mountainous, which is prone to flooding and landslides. There is a need for some sort of settlement plan, to avoid places that are hazardous during extreme weather events like cyclones.

What was your intent by applying for the CDA? What is your solution?

Kudzaiishe: Two things were needed. One is more education on climate change and how to mitigate or adapt to it, tailored to the local population. Most people don’t think about climate change, especially in the rural areas, because they are uninformed. We did a survey that showed that only one out of five people in the Chipinge District are aware of climate change. They think the droughts are a result of “bad luck.” The problem that comes with lack of communication is that when the government comes with projects to address adaptation or mitigation, people don’t participate.

The second need is a customized policy shaped by the people. Zimbabwe already has a national policy, but it's too generic. Zimbabwe has 16 million people in 10 provinces. Each province has its own, unique climate-related vulnerabilities.

In addition, the people must be heard about what they think the highest priority challenges are, what local policy should include, and how they can partner with the government to make it successful. Without the people saying what they want and need, successful follow-through might be difficult.

For example, the most powerful people in rural Africa are the chiefs, or the traditional leaders. If we want resources mobilized faster in a disaster, they must be included in the plan, along with religious leaders, local councilors, members of parliament and government departments. And among the partners must be local radio stations. Sixty percent of Zimbabweans live in rural areas, where the internet is not readily available, so community radio stations are really important.

We also wanted to make sure that both IDPs and the refugees of Tongogara were included. They are too often left out. We have learned that although their challenges are similar, our refugees and IDPs require different approaches. The refugee camp has an organized youth group that is fairly educated about climate change. In contrast, most of our IDPs are rural dwellers with low education and little access to environmental agencies that help them understand what climate change is. Plus, unlike the refugees, who live with their families and can be gathered all at once, the rural people live in very dispersed, mountainous areas.

What participatory process did you choose to develop this shared plan?

Kudzaiishe: We decided to try participatory policymaking. Historically, Zimbabweans have not been significantly included in public policymaking especially in rural areas. I thought that this created a significant gap, especially in climate action. The people had only helped the government roll out national climate policies; we had not been engaged in initiating anything.

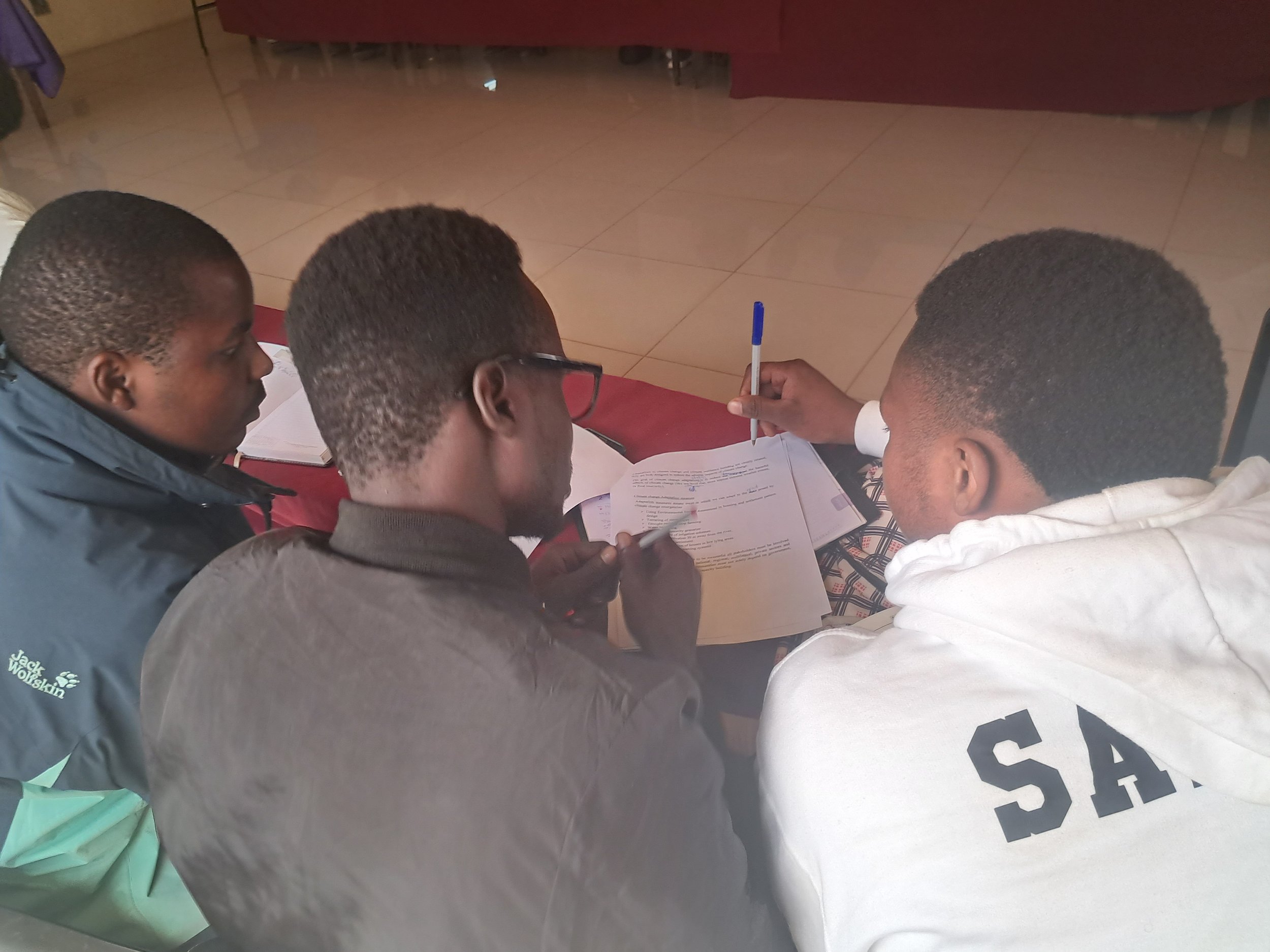

Several Zimbabweans convened by the Green Institute provide input into a local plan.

Why was it important to you to have a mentor?

Kudzaiishe: The biggest challenge for us was lobbying government authorities to try participatory policymaking. Although we already had a good relationship with the rural district council and other government bodies, we know it’s always difficult to introduce a totally new process. I wasn’t sure how to approach that.

Also, I wondered how to mobilize community members to participate, since this is a fairly new process, which they’d never heard of. The third challenge was how to start: the top or the bottom. Start at the community level and push upward or at the district government’s development committee and go down?

What makes participatory policymaking unique?

Mateusz: We’ve been doing participatory policymaking since 2011, beginning as a team of sociologists at the University of Warsaw. I see participatory policymaking as the broadest, most flexible type of citizen engagement. Strategies such as legislative theater, participatory budgeting and citizens’ assemblies have specific rules and methodologies. In contrast, participatory policymaking is broad and flexible, simply calling for deliberation in community spaces, then connecting it to decision-makers and policy. It’s important to note, however, that it’s not about dialogue alone, like building bridges between neighborhoods or neighborhoods and government officials. It always must be connected to decision-making, to making better policy.

You’ve mentored a lot of people. What made this ‘pairing’ special for you?

Mateusz: I’ve been a mentor to other, smaller organizations in Poland, about 20 or 25 times. What was unique about this mentorship with Kudzaiishe was the use of the Participation Playbook . For me, this first cohort (of the CDA) was kind of a pilot of the playbook. The mentorship was a combination of conversation and doing the playbook together. It was really fun, actually!

Before the playbook was available, I could only talk about the idea with my mentees, and read articles about participatory democracy methods. The playbook offers an interactive way to teach the methodology. But even more importantly, the playbook forces users to start by defining the problem they want to solve, rather than the tool they think they want to deploy. The former must be understood to decide the latter. And the playbook provides a very structured way of doing that.

I also want to say that the international exchange part (in this case, the sharing of experiences between Zimbabwe and Poland) in the context of managing climate change was new for me. I have often wondered whether certain participation tools are limited to certain geographic contexts. What Kudzaiishe showed me is that even in a difficult climate context, public participation is a good solution. There is real value in thinking together.

Do you think the Participation Playbook is effective alone, or is it best used with a mentor?

Mateusz: I think it's really a good idea to make the playbook publicly available. For example, professionals in Poland, such as officials in city halls or experts from NGOs, will really benefit from the “sequencing” the playbook offers. But at the same time, you want to make sure people make the best decisions. And that’s where a mentor comes in.

Kudzaiishe: I'm a really curious person, so as soon as I was accepted into the (CDA) program, I went through the whole playbook. I didn’t wait for a mentor. However, when I went back through it, Mat really added value.

I’d sum up the playbook this way: It's both simple, and overwhelming. The mentor helps with the overwhelming part, as well as functions as a sort of propeller — driving you to achieve things.

What were some of the challenges and lessons learned from the CDA and the mentorship process?

Kudzaiishe: I often had internet problems, so we also worked via WhatsApp and email. It is important to have multiple ways to communicate.

That was true for our project as well. For all of or target groups, we kept everyone updated via text and WhatsApp. And in the rural areas, where there’s not much Internet, we used radio shows. People really listen to the radio. We have a slot every Saturday from 3-4 p.m.

Mateusz: Yes, it was a good experience for me to learn how to work with external limits like blackouts during an energy crisis. What is ideal with the playbook is that as Kudzaiishe’s “partner,” I could see his answers as he worked through the questions. That’s a really nice feature.

Kudzaiishe: I’d also say that mentees must recognize that you are still learning, sort of going back to school. Although I often raced ahead in the playbook, I learned that I really needed guidance. It’s important to accept that.

I also learned that it was very helpful to keep records of what you discuss and commit to in each session/exchange. Mat always referred back to what I said/agreed to maybe three sessions ago, and thus kept me “honest.” I learned to be realistic and truthful in my action plans. It requires serious commitment and serious follow-up with your mentor.

One final thing: When we were talking about funding the project, Mat asked about sources of money. Mat knew that the $20,000 implementation grant I got via the CDA would probably not be enough. And a lot of us have the mindset that the governments of poor countries like Zimbabwe struggle to fund these kinds of initiatives so we don’t even ask. But Mat encouraged me to get all the stakeholders on board, recruiting them to buy in and fundraise for some of the resources we might need. So, I found some other calls for climate projects and I applied, and was able to get what I needed.

A final participatory policymaking meeting conducted by the Green Institute.

Mateusz: I’d add this: From my perspective, in most cases, participatory policymaking should be done as part of working together with decision-makers. That's why it was really important for Kudzaiishe to think not only about the sources of funding, but also the sources of knowledge and power to bring to the table.

What is the current status of the participatory climate policy?

Kudzaiishe: During the co-creation process, all the stakeholders in the community wanted to be involved. But that produced a lot of raw data. So, we engaged a consultant who developed the policy based on that. During validation, we went back to everyone with that policy and asked them to weigh in, to ratify it. Now the rural district council and the traditional leaders must implement it.

Among the measures outlined in the policy are actions such as:

Mitigation

Use of clean energy such as solar energy, biogas and hydropower.

Use of public transport such as buses and cycling.

Afforestation.

Adaptation

Terracing of steep slopes.

Planting of drought-resistant crops.

Irrigating to supplement rainfall

Reforesting.

During implementation of the policy, we will conduct an annual review process. So we'll be reviewing how this is working. For example, the policy urges traditional leaders to distribute copies of the policy on climate change. We’ll want to go back to the community and do some surveys to see if the numbers of people who are informed has increased.

As for follow-through by the authorities, the central and local government authorities suffer from a lack of funds. In addition, governments generally, in all developing countries, have a reputation of being inefficient and not very responsible. But I expect to see the government triggered into taking some action specific to people’s needs. I believe participatory policymaking will prove to be a disruptive policy. The people themselves now feel part of this whole process. They had become used to the idea that policy comes from the top. But now they are involved.