Digital democracy: How do we assure that the online 'revolution' is mostly promise, not peril?

/People Powered recently launched a new accelerator program focused on “digital democracy,” funded by the Open Society Foundations. Via the accelerator, 12 applicants from Europe will be selected to get expert mentorship as they develop an action plan for engaging citizens in developing more just and equitable digital policies, then receive a grant of $15,000 to implement the blueprints. What are some of the digital issues that need this kind of focus and would benefit from an infusion of participatory democracy?

People Powered Communications Director Pam Bailey interviewed Reema Patel, research director and head of deliberative engagement at Ipsos, policy engagement lead for the ESCR (Economic and Social Research Council) + Digital Good Network, and an associate fellow at the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence, a research institute exploring the impact of AI. Previously, she was an associate director for the Ada Lovelace Institute, an independent think tank seeking to ensure that data and AI work for people and society. Reema serves on the People Powered expert committee guiding the Digital Democracy Accelerator and is one of the mentors working with participants.

Just what is “digital democracy”?

Reema Patel

I don’t believe we should consider digital democracy a separate type of democracy. There really is no aspect of our life that is not permeated by the online revolution. If we're interested in democracy, then we must be interested in digital democracy.

You know, when I started off in this space about 10 years ago, online tools for engagement were a new thing. But now, we all use tools like WhatsApp. So, the real question is, how do we have the next-level conversation about digital democracy? For example, Evgeny Morozov, who rose to prominence by talking about online surveillance in Spain, has written about slacktivism and the impact of digital discourse on people's ability to engage in really deep ways. His point is that as we rushed to adopt tools such as e-petitions and online campaigning, our engagement has become shallower, rather than deeper. Another thinker in this arena is Martin Moore, who wrote a book called “Democracy Hacked,” which examines the generation and spread of disinformation. He analyzes the collection and use of large-scale datasets, such as that created by Cambridge Analytica for Facebook, to profile people and influence the way we vote, through micro-targeting.

On the other hand, technology can play a significant role in enabling deeper conversations, unlike what Elon Musk is trying to do with Twitter. I think this is an mportant conversation to have, rather than just how to prevent harm – which is where we seem to be stuck right now.

How did the COVID pandemic expose both the peril and promise of digital tools, and democracy?

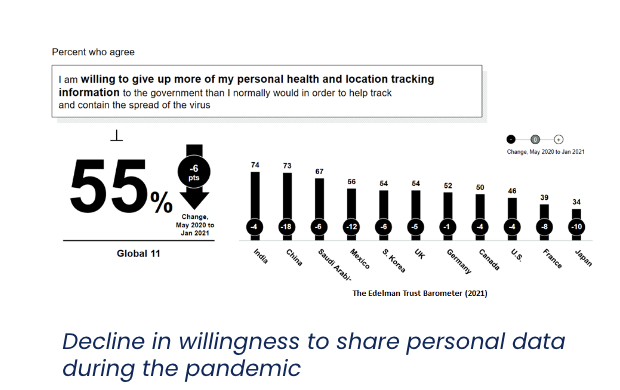

The pandemic really affected how digital data and artificial intelligence (AI) are used and perceived. Their use really ramped up, but people became less willing to share their personal information.

At the same time, the pandemic brought into the spotlight the inequality between different groups of people. It has become obvious that decision-making related to digital issues and policymaking requires deeper, systems thinking. And public participation can help policymakers and technologists understand what responsible use of AI and data use looks like, and also address inequality.

Recently, I wrote a chapter for a book about pandemic-era changes, such as the use of vaccine passports. Such passports use a very hyper-specific technology, and I was involved in asking what people think is okay, and what’s not okay, when it comes to collecting and sharing this type of information. The other, related area we got involved with was risk-scoring. Those technologies were developed and implemented without having conversations with the public about whether that was ok. These are important societal conversation to have.

What concerns you the most in this space right now?

One that comes to mind is that a democratic system should work for everyone, so digital exclusion is a really strong concern. There's an assumption now that everyone has access to the fundamental infrastructure required to be able to participate online. But that’s not true and the risk is that participation will only benefit a very narrow group of people. For example, I've been at the forefront of online deliberation in the UK, but I wouldn't recommend it to engage farmers in Colombia. We need place-based approaches that consider both risks and equity.

Photo courtesy of Unsplash

I wrote a piece for the Ada Lovelace Institute called “The Data Divide.” It sets out how we’ve created datasets based on people who use symptom-tracking apps, but those people tend to be a very early-adopting population with access to superfast broadband, etc. In other words, they are not representative. And we don't know what we don't know. We want our political decisions to serve everyone.

Another concern is the undemocratic use of digital tools. Although there are some notable exceptions, most policymakers are not thinking about digital advancements as tools to advance democracy. Rather, they're thinking about them as ways to shape behavior, to surveil and to control. When you're looking at the use of these technologies by politicians, they're not using them to expand people's locus of control. They're using them to expand their own ability to control and influence. It doesn't seem like progressive politicians have woken up to this risk. The popular narratives come from privacy and surveillance campaigners, not from democracy activists.

The obvious example of the potential danger is facial recognition technology, the biometric space, where it's really clear that the power dynamics are very problematic. For instance, in the UK and West Midlands, police forces are using very different approaches, from “we're running live facial recognition technology, period” to “we recognize this is really challenging to our community and we want to set up an ethics committee and a community engagement panel to make sure our use of this is appropriate.” Nevertheless, the competition is still all about how can we best use the technology, and not “maybe we should pause it first.”

The only organization I know of that’s having that high-level conversation is the European Commission, because the EU AI Act, in its current form anyway, bans facial recognition technology. The German Data Commission also recognizes that predictive analytics is a technology that might have a high-risk impact on people's lives. For example, using predictive analytics for criminal justice purposes falls within that category, because if use of that data resulted in wrong advice, that would have a huge impact on the criminalization of a particular group of people.

What about the use of artificial intelligence?

The risk is that we don't look critically at the sources on which AI is based. Ultimately, AI is trained on data, which itself comes from biased sources. As a result, I think we're a long way away from being able to say with great confidence that artificial intelligence is able to moderate content on online participatory platforms. We’d need to ask questions like what datasets was the artificial intelligence trained on? Do the decisions on which those datasets are based reflect what we want for society?

A lot of debate is centered on “fake news” or disinformation as well.

Yes. There’s a great risk that content moderation laws will be set by governments, resulting in the perpetuation of a single narrative of what truth is -- the exact opposite of what we want. True, there are ways to identify content that is obviously fake, like answering the question, “Did the depicted event actually happen?” We can bring evidence to that. But then the separate question is, who should govern that process?

Outside of the obvious deep fakes, the issue is who should decide what is acceptable. Should it be the members of a community? Or should we expect the creators of a platform, like Facebook, to practice self-governance? I’d say developers should not be the arbiters of how we have our conversation online. Sure, there are some obvious “wrongs” we can identify, like exploitation of children. But other things are just people expressing who they are online. We need to have that conversation. We must avoid a one-size-fits-all approach and making the technology developer the moderator.

Could participatory democracy be used to assure these policies are responsive to the needs of impacted people?

Yes! But let’s pay attention to who commissions it. The power holders are often the sponsors. I’d like to see a really important role played by independent parties, such as civil society organizations. Unfortunately, there is a narrative from certain sectors that says that if a policymaker hasn't commissioned a particular deliberative process, it's somehow not valid. I really take issue with that. Independent organizations will often tackle issues that policymakers are very reluctant to take on. For instance, when I was at the Lovelace Institute, we did a whole load of work on facial recognition technology and biometrics that wasn’t resourced within the UK government at the time. We chose that issue because we knew that unless we worked on it, nobody else would. And sure enough, three to four years down the line, we were asked to brief the UK home office.

Even though I am a deliberative engagement practitioner, my view is quite non-mainstream in some respects. Most deliberative engagement practitioners think juries, etc. need to be commissioned by a policymaker to have traction. I'm less convinced about that. And there are a lot of academics and researchers who are now calling for what they call an ecology of participation, in which participatory initiatives are defined bottom up.

What do you hope comes out of the People Powered accelerator program?

I hope that collectively, the participants problematize where we are in this moment and tie it to why this is difficult for democracy. I don't think that leap has happened. We also haven’t made the leap from the problem to, “Here's what we want to see. This is what a good use of digital technology in our democracy could look like.” The conversation to date has been simplified to a focus on online harm.

There are a few people who are doing what I think needs to be done, but they are being treated as “fringe”– such as Evgeny Morozov. We need to engage with the fact that the technologies we thought would be good for democracy have not been. There is still a kind of digital libertarianism that is prevalent in Silicon Valley, a belief that the internet and all the related technologies will democratize the world. Now, I don't mean to dismiss the good that has come from it. We have far more access to information than we would have had without it. But we also have far more problems than the early pioneers anticipated. It would be good to see some of the accelerator programs amplify the work of the individuals and organizations are trying to raise those concerns.